Mesa Verde is a national park and UNESCO World Heritage Site located in southwestern Colorado. Best known for the numerous cliff dwellings dotting the sides of the mesa, it was originally established as a national park by Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, with the park occupying 52,485 acres and, with more than 5,000 sites, is the largest archaeological preserve in the United States (Mesa Verde National Park). However, Mesa Verde has a rich history long before it became a national park. Even its establishment as a park has its own story.

Occupation of the Mesa Verde region can be traced back thousands of years. It was primarily a hunter-gatherer society until around 2200 BC, when there is evidence of the first known domestication of corn in the region. Though the people at the time were still practicing the Archaic hunter-gatherer lifestyle, the domestication of corn is a clear sign of a shift towards an agricultural based society.

It is generally agreed that shift from hunter-gatherer to a primarily agricultural lifestyle, marking the beginning of Puebloan culture in Mesa Verde, was between 500 and 400 BC. The shift includes the creation of more permanent dwellings. These structures, not cliff dwellings, were pithouses – semisubterranean structures that served as houses for individual families. This group, called Basketmaker II, lasted until around 500 AD, which was followed by the Basketmaker III group. This group included numerous advancements, including the development of great kivas and roomblocks – above ground, contiguous storage rooms – new pottery technics, notably grey and white ware and red ware, and the domestication of new crops, such as cotton.

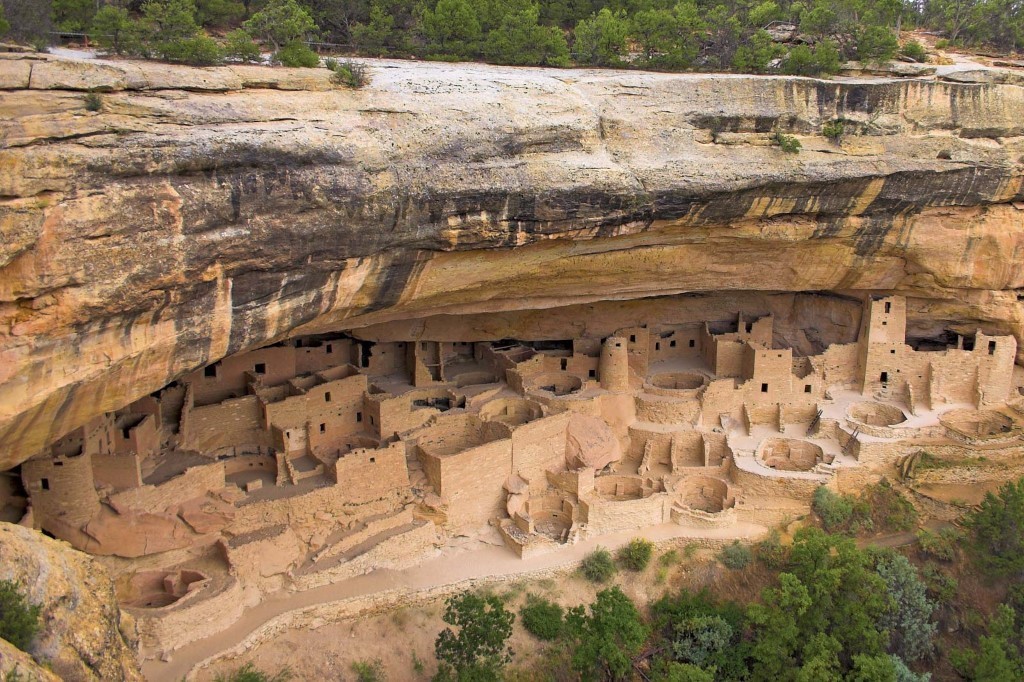

The first Pueblo villages, defined as settlements with more than 50 rooms, began appearing around the mid 8th century AD and marks the start of the Pueblo I period. There was a dramatic shift in architecture, as the first masonry style – stones stacked vertically and held in place by mortar – constructions began appearing, as well as the shift from pithouses to kivas as the primary focal point for household activities. Pueblo II, which began around 900 AD, saw the growth of trade networks, especially through Chaco Canyon, a major cultural and economic hub of the Ancestral Puebloan world in modern day northwestern New Mexico. Finally, we have reached Pueblo III, which is generally defined as 1150 to 1300 AD. Almost two hundred years after its grand rise to prominence, Chaco Canyon, and the rest of the Four Corners region, experienced the longest and most severe drought in the region’s history, causing a rapid waning of Chaco’s influence as people migrated away. A number of these people traveled to Mesa Verde, where, in 1250 AD, they hit their population peak. It wouldn’t last, however, as drought, temperature change, and warfare all led to a mass migration and the decline of Mesa Verde, with the region being almost completely deserted by the end of the 13th century. The Pueblo III period is curiously short, lasting only 150 years, but also saw the building of the cliff dwellings, an impressive feat, only for them to be abandoned shortly thereafter.

After the mass migration away from Mesa Verde in the 13th century, the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde sat empty for hundreds of years. The Ute tribe, who lived in western Colorado since at least the 1400s, did not settle in the empty houses. In describing the dwellings to Richard Wetherill, a rancher, one member of the local Ute tribe said, “Deep in that canyon and near its head are many houses of the old people – the Ancient Ones. One of those houses, high, high in the rocks, is bigger than all the others. Utes never go there, it is a sacred place,” (Wenger 79). Over the years, Mesa Verde was visited by various explorers and pioneers, even gaining its name from two Mexican-Spanish missionaries seeking a route from Santa Fe to California in 1776, who recorded their travels and named the region after the tree-covered plateaus, though they never got close enough to see the cliff dwellings. The land of Mesa Verde, and all of the Colorado land west of the Continental Divide, was formally recognized as belonging to the Ute tribe by the United States in a 1868 treaty. However, only a few years later in 1873, the US government changed the agreement, giving the Ute tribe a strip of land in southwestern Colorado that contained most of Mesa Verde. Both treaties were caused by gold and silver being found in the Rocky Mountains, with gold and silver later being found on the western side of the Rockies causing the second treaty.

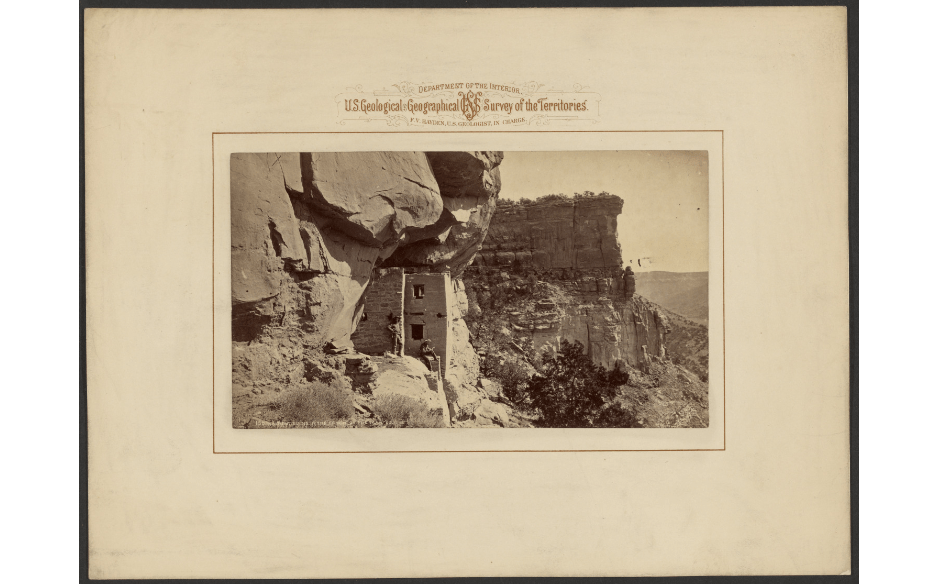

Though it is unclear who first “discovered” Mesa Verde, it was William Henry Jackson who first recorded the cliff dwellings on film. In 1874, he photographed a number of cliff dwellings and even gathered some pottery pieces, which he sent to the National Museum. Afterwards, a number of other people, including geologist William H. Holmes, and journalist Virginia McClurg, visited the dwellings. However, it wasn’t until Richard Wetherill came along in 1888 that exploration of the sites really began.

Richard Wetherill was a rancher in Mancos, Colorado, and his family had set up an agreement with the nearby Ute tribe, which allowed them to bring their cattle onto the tribe’s land. While there, they found a number of smaller cliff dwellings. On December 18, 1888, Richard Wetherill and Charles Mason, a fellow rancher, spotted the large dwelling that Wetherill later named Cliff Palace. The same day, Wetherill also managed to find Spruce Tree House, and the next day Square Tower House. All of these dwellings, as well as the names of the mesas themselves, Wetherill and Chaplin, remain their names today. For years, the Wetherills, as well and their friends and neighbors, collected and sold thousands of artifacts from the ruins, with most of them ending up in museums.

The Wetherills’ rough exploration and excavation continued until in 1891, Gustaf Nordenskiöld came. Nordenskiöld was a Swedish mineralogist visiting the States in an attempt to ease his tuberculosis. However his tour was cut short when he heard of the number of cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde and, upon seeing them himself, decided to settle in Colorado for a time to research and document the ruins. Nordenskiöld, with his background in minerology, actually brought a degree of scientific method to the proceedings, and conducted the first archaeological excavation of the cliff dwellings. However, along with the over 150 of pictures that he took during his time in Mesa Verde, Nordenskiöld also took hundreds of artifacts from the sites. At this time, there were no laws in Colorado against treasure hunting, so Nordenskiöld was legally allowed to do so. However, his looting of so many artifacts caused an uproar, which ended with him even being arrested, although Nordenskiöld was far the only person looting the ruins. The Wetherills had been doing so for years now and, as knowledge and interest in the dwellings spread, so too did people coming to tour the area, many of whom took artifacts from the sites as trophies. Needless to say, xenophobia played a role in Nordenskiöld’s arrest, though he was eventually released as he had not committed an actual crime.

Nordenskiöld soon returned to Sweden, where he wrote a book on the cliff dwellings, The Cliff Dwellers of Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado: Their Pottery and Implements, while the artifacts he shipped back to Sweden were bought by a Finnish collector after Nordenskiöld’s death, who eventually donated them to the University of Helsinki. They later moved to the National Museum of Finland, where they resided until very recently. It was announced in a meeting in October 2019, though the actual process had been prepared for years, between Finland President Sauli Niinistö and US President Trump that the National Museum would be returning the remains and some of the artifacts to Mesa Verde. Finally, in September 2020, the remains and artifacts promised were returned to Mesa Verde, with the Hopi Tribe in northeastern Arizona, and Zuni, Acoma and Zia pueblos in New Mexico having been involved in the process and have since reburied the remains of about 20 bodies taken from Mesa Verde by Nordenskiöld.

As for the park itself, efforts were made over the years to get the government to grant federal protection to the area to styme the flood of artifacts from the area. In a report to the Secretary of the Interior, Smithsonian Ethnologist Jesse Walter Fewkes described the vandalism of Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace:

No ruin in the Mesa Verde Park had suffered more from the ravages of “pot hunters” than Cliff Palace; indeed it had been much more mutilated than the other ruins in the park. Parties of workmen had remained at the ruin all winter, and many specimens had been taken from it and sold. There was good evidence that the workmen had wrenched beams from the roofs and floors to use for firewood, so that not a single roof and but few rafters remained in place…Many of the walls had been broken down and their foundations undermined, leaving great rents through them to let in light or to allow passage from the débris thrown in the rooms as dumping places. Hardly a floor had not been dug into, and some of the finest walls had been demolished. All this was done to obtain pottery and other minor antiquities that had a market value. The arrest of this vandalism is fortunate and shows an awakened public sentiment, but it can not repair the irreparable harm that has been done. (Fewkes)

In order to protect the ruins and artifacts held within, spurred on by the loss of so many artifacts to Sweden by Nordenskiöld, congress passed the Federal Antiquities Act in 1906, and in the same year President Theodore Roosevelt approved the creation of Mesa Verde National Park, becoming the first national park established for its cultural significance (Rancourt).

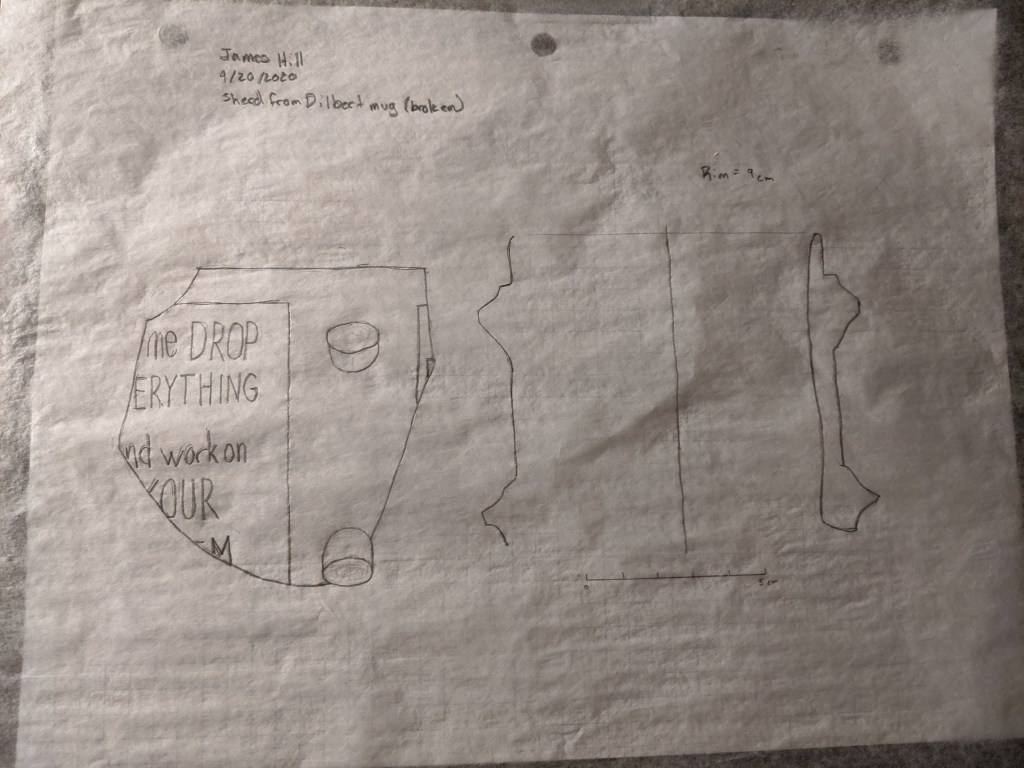

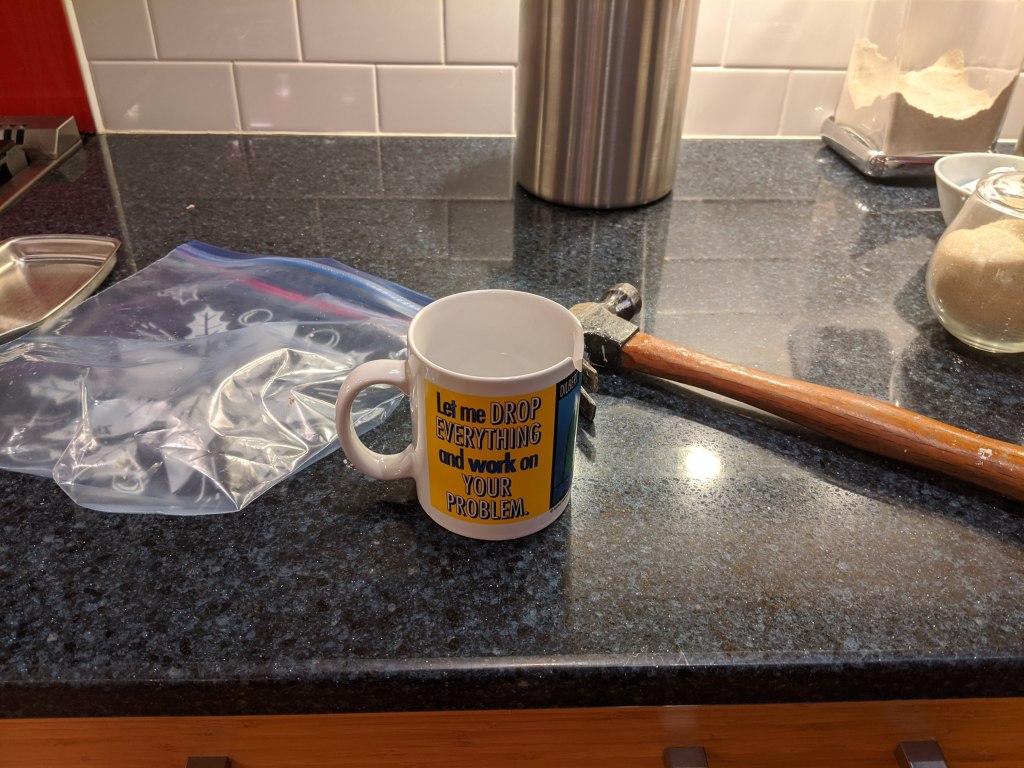

Today, over a hundred years after its instatement as a park, Mesa Verde has served its purpose as a protection for the artifacts and archaeological sites within from the worst of the looters. However, it is important to think about what we can learn from the park’s history and what we can do moving forward. While the park no longer suffers from the rampant looting that led to Fewkes’ gut-wrenching description of the state of Cliff Palace, there is still a casual form of looting that most look over, even the looters themselves. Although most of the artifacts within the archaeological sites have been brought to museums for care and study, it is still possible to find the occasional pottery sherd. In my own visit to the park, while I was walking around one of the more out of the way sites, I found a number of sherds scattered around on the ground where anyone could pick them up. I’m sure that any number of people who visited that site would see the sherds and take one with them as a souvenir or a way to remember their trip. However, this severely damages the archaeological record and is, at its heart, still looting. But most people would not think of it that way, as they have never been told otherwise. I think it is important for there to be information around, such as in the museum, that discusses the damage of looting, as well as signs near sites. While this may not stop the most determined or oblivious person, it will serve as education for the wider population, who may not know that taking artifacts, even artifacts as small and seemingly insignificant as pottery sherds, is harmful. Overall, I believe that by educating people on the history of Mesa Verde can impress upon them the importance of archaeology, history, and understanding not to take any artifacts they may find on the ground when they visit these sites.

Works Cited

Fewkes, Jesse Walter. “Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park Cliff Palace.” Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park: Cliff Palace, by Jesse Walter Fewkes – A Project Gutenberg EBook., www.gutenberg.org/files/42266/42266-h/42266-h.htm.

“Mesa Verde National Park | World Heritage Site | Discover a place that time has forgotten” (PDF). Visitmesaverde.com

Rancourt, Linda M. “Cultural Celebration.” National Parks, vol. 80, no. 1, Winter 2006, p. 4. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=aph&AN=19505113&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Wenger, Gilbert R, and David W Wilson. The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Fourth rev. print ed., Mesa Verde Museum Assoc, 1999.

Images Used

Jackson, William Henry. Ancient Ruins in the Cañon of the Mancos. 1874.

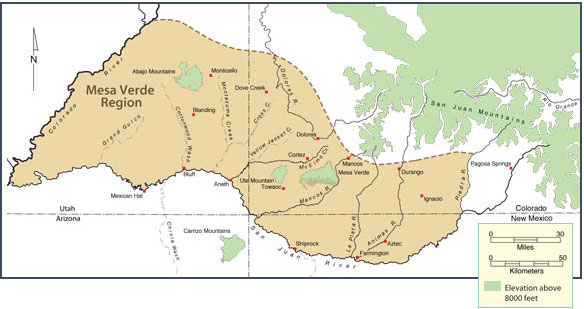

Morris, Neil. “Map of the Mesa Verde Region.” Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, 2014 Peoples of the Mesa Verde Region [https://www.crowcanyon.org/EducationProducts/peoples_mesa_verde/intro.asp].

Nordenskiöld, Gustaf. “Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde, Southwestern Colorado.” Gustaf Nordenskiöld and the Mesa Verde Region, Colorado Encyclopedia, 20 Aug. 2015, coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/gustaf-nordenski%C3%B6ld-and-mesa-verde-region.

Watkins, David. Cliff Dwellings: Cliff Palace. Mesa Verde National Park.